Unmasking my Neurodivergence while I Raise a Son with Autism after Loss

Everyone wanted Alice without wonderland. If I saw Neverland, they wanted me to leave and declare before all that it was impossible to fly. Sparkle dust and rabbits with gloves were fairy stories meant for a very short time. ~ poem from A Messed Up Kind of Beautiful by R.A. Bridges

I knew from an early age something was different about me.

As a child, kids made friends so easily. I rarely did, and when I succeeded I tried to keep them. I wondered why some girls made friends, and I could not.

By the age of six, a person with autism will experience more negative interactions compared with other children.

Until I saw the almost 100 pages of documented testing performed with me as a four and five-year-old, I couldn’t understand. Then, I did, once I read everything in April 2020. I was recommended for further testing with autism in early ‘90s.

The testing of a girl in the South for autism in the ‘90s was an unspoken “No, thank you, darling.”

Would a diagnosis have changed things? I don’t know. My parents wanted to help, but not label me. My father, especially, didn’t want me labeled nor in special education classes. My mom was a teacher, and while I’ve often disagreed with her on almost everything, she fought hard to offer me the best education possible.

Learning to Mask

I grew up learning some hard lessons. They changed me from a naive, daydreaming, sing out loud child to an adult who questions motives, finds comfort in being alone–especially in nature–and distrusts most people. I don’t view those as bad points. I imagine them as strengths and shields. I learned how to mask when I needed.

You’re a child with a different kind of mind. You forget the horse droppings underneath the creatures’ hooves. The wheels run over feces, and muck sprays the road side. If the wheel gets stuck in the mud and rain, does the fairy godmother cover the insurance? And when Cinderella leaves her slipper, why doesn’t she ever fall? ~ from the poem "Beyond the Lemonade Stand" from the collection, Cherry Blossoms on the Road Side by R.A. Bridges

I was a small town news reporter in the days when newspapers were still tripping over rocks to try be more than backwoods’ toilet paper in the rise of social media. I developed the skill to ask others about themselves. Investigate, dig, and get any spotlight off yourself.

This will help you mask.

Questioning also allowed me to examine others and the social rules to which they adhere. I need to get a feeling as to whether you might feel comfortable enough around me; no matter my neurological differences.

Then, depending on the person, I judge how much or which side of my personality to show. If I think a person is non-responsive to say a text or one invitation out once, I never text or ask again. This might seem extreme, but seen through the eyes of one who has faced social rejection, it’s not.

This sounds like a lot, but it’s learned behavior for someone who is neurodivergent, but I also wanted to set an example for our son, Hayes, now 13, who is diagnosed with autism and ADHD.

A Neurodivergent Mother with a Child with Autism and a Child in Heaven

In some ways the road is harder for Hayes, while easier in others because of the services he receives.

As Hayes has grown, I avoid sharing recent pictures of him, his feelings on certain matters, and respect his privacy. There are some facts and stories about him I can share.

Hayes—as I call him in writing—struggles with those daily social skills, reading, writing, shares the desire for a friend, and he is my entire world on Earth.

My husband, John, says the lioness will come out quick for her cub, and he’s right. It’s not that I don’t hold our son accountable for his actions. John and I both do.

But, when our daughter Corrie died suddenly on May 27, 2020; I blamed myself. When I miscarried in February 2021, I blamed myself. My greatest desire in life was to become a mother, but how could I be with two in heaven?

Was I less of a mother because a part of my brain was different? Was I not “quick enough” to spot the tumor? Am I somehow unworthy to be their mother, too?

These thoughts played through my mind after Corrie’s death and the miscarriage.

Corrie never struggled socially. By eighteen months, she’d been tested for autism, only because her brother had just been diagnosed. She was more like John in all the best ways.

One time a student asked, “Mrs. Bridges, you always talk about your son. But what about your daughter?”

“I tell you about my son, so you will understand autism,” I replied, and I smiled. “Other than her health during the winter, I don’t worry as much about Corrie.”

“Why?”

“Because Corrie is ready to take on the world. She’ll put a guy in his place real quick, and one day she’ll be a CEO.”

The world and its doors automatically opened for my daughter with just a smile. She could read people as early as three, and play on them because her language was well developed. Many children showed up for her birthday parties, while we took Hayes on road trips to the beach every June for his.

This never made my son any less.

It never meant that John and I doubted Hayes could also achieve those same dreams at all. If anything, I always thought I’ve been through this. I’ve been laughed at, and isolated. I can help him.

I knew what it felt like living as someone who is neurodivergent. I knew what it was like to struggle with reading. My paternal grandmother started me early with Hooked on Phonics. My Kindergarten teacher wrote that “Rebecca starts stuff with other kids, but I can’t figure out the reason.” She told the doctors, “She’s interested in stories,” but “she lacks depth [in answers]”—(for those who know me will laugh hard at this)–”and imagination.”

I also stuttered when I spoke at times and read.

When we lost Corrie, it ripped something unseen from us, besides her. It tore apart our family picture, and it affected three people in different ways.

Hayes started to bury the pain, and tuck it down deep, except around me. It was too, too deep.

By age ten, only a few weeks after Corrie’s death, he understood that people already don’t understand him. He already understood that he was diagnosed with autism, and he never learned to mask the way I did.

Add his sister’s death. He, like me, believed: If they don’t want to try and understand someone with autism, they will not touch someone in grief over their sibling. In three years, he’s only had three public reactions or outbursts about her. Those were all within six months following May 27.

I had to somehow pick myself up, teach and raise our son with this new mix of struggles. I was frozen. He needed help with his academic subjects, and I was torn between heaven and Earth.

His reading was already behind, and I was losing my mind. His math seemed to also fall behind, and John was diagnosed with colon cancer. He was socially struggling, and I was commented on and judged harshly and repeatedly by three former acquaintances during this time, while supported by everyone else.

Last year, I came up with a saying:

If you feel you can walk and manage this path better than me, please step to the front of the room. Speak to me of your knowledge and experience.”

The shared sarcasm of my husband, son and I had aided us through many moments when tears would otherwise enter our eyes.

There are those who assume they know you: you’re too sensitive, or will explode if they say the wrong thing at the wrong time. They never realize you’re blending the foundation before they see your face, and you build walls and vaults, so they’ll never see your heart and mind. You develop the ability to cut them off. Delete the number in your phone, and forget their face. They will never understand your Neverland. ~ Verse from the poem "October Passing By" by R.A. Bridges

I always loved my children equally, and believed in both of them. I held Hayes accountable, and became his biggest cheerleader because not many others would.

While I’m now contemplating different educational options for him, Hayes was blessed with something extremely important. From the time he was in preschool, he had excellent teachers. I mean top-notch, genuine, caring, but firm individuals who affected Hayes through the sixth grade.

My child is far from an angel, but he also has his own great light to shine. These teachers are constant reminders, and lights flickering in the distance on an otherwise dark night. Because of their memories and fondness for him, it gave him strength to navigate other times.

Your sunrise will come again as you wander in the land between swamps and shadows; the lands without friends. I hear you say to strange children at the pool, "I love you,"or "Will you be my brother?" I bore my eyes through them like insects that eat through skin when one says, "I told you, 'I don't want to play with you.'" ~ from "Your Sun Will Rise Again" a poem from the collection, When We Danced in the Rain by R.A. Bridges

Autism Spectrum Disorder, or ASD, is just as diverse as the human population. Individuals diagnosed with ASD, or others, differ just as much learners in the gifted-and-talented population or artists. Hayes was diagnosed in 2015 with ASD 1, sometimes referred to as high functioning. He and I have had a lot of honest conversations about it.

Some of his behaviors stem from his ADHD, while others come with the ASD. This includes his noises and repeated questions. He’s thirteen now, and knows the noises disrupt, and his previous teachers, John and I worked as team to limit and reduce the noises.

Right now, he has this desire to be funny in a way that isn’t and disrupts. The reason behind it is because he wants to make people laugh, so that they never feel the pain he continues to experience daily with his sister gone. His memory calls up the backset conversations they had while on the way to school. It was nonsense, but she was there. While he doesn’t mask his autism, he masks his turmoil from everyone because he learned something early on from me.

Be careful of who you trust.

Through sixth grade, Hayes built trust with his special education teachers where he would exert more effort and share some feelings. John and I each have different favorites in this mix, but we agree that during these times, they all gave Hayes a strong foundation.

In preschool, his first real teacher began to identify the differences in him. At the time, Hayes was only 3 to 4; too young at that time for testing autism.

As a child with limited language, expression, or understanding of emotions; he got angry one day. At age three, he pushed a table into this teacher. It knocked her down.

I thought the world would end.

My early learning looked different in that I was not as physical as Hayes. I had the same language struggles. When I read aloud, I still stutter some words, which is why I use recording in my English classes.

But where the preschool teacher told my parents, “Rebecca is different from the other children”; Hayes’ teacher—who I’ll call Mrs. Schaeffer—gave him the appropriate consequence. We did as well.

Mrs. Schaeffer didn’t give up on him. She helped guide him and us towards what we needed and could do in his early education. She came to his first IEP meeting as he transitioned to public school.

His second and third grade teacher (first run through) I’ll call Mr. Bernard. By that time, Hayes didn’t have the behavioral struggles rearing their head. It was the reading, math, and writing.

Mr. Bernard called John and I only days after Corrie died.

John handed me the phone. He said, “He wants to talk to you.”

I took the phone.

“Corrie had a special light, but you remember Hayes does, too. Hayes has a special light of his own to shine on the world.”

I never forgot that.

I remember that now when:

Hard days gone; only more are comin.’ I can’t seem to find my running shoes, and I’m tired of using old fighting moves. I long to take off the gloves, hang them on the wall, and forget, forget I needed them at all. My daughter’s body laid in the ground, my husband survived when the cancer came, and reactions to our son’s autism wax and wane. The noises and questioning of some teachers increases when before they were under control. I know, by now, to parent a child with a different and beautiful mind means hard days are comin.’ Darkness is on the rise, and I stopped praying for strength long before she died. For am I not Job? I believe even on the hard days comin,’ the sun will rise. ~ Verse from a new poem, "Hard Days Comin'"

I remember Mr. Bernard’s words now as we face new challenges in Hayes’ education and behavior, as John and I both work to raise a young man who will make everyone proud. I wish for a Mrs. Schaeffer or a Mr. Bernard right now because they worked miracles. They knew Hayes could and would read and write if that relationship was forged first.

Where our son faces consequences for his actions, we’re also working on building his confidence and self-belief. I can share this. Right now, he believes the wrong child lived. No child should ever believe that.

I remind him that I was a child who didn’t speak until late, too. Certain letters didn’t come through until later. When a preschool made my parents unhappy because I was viewed as “less” due to my neurodivergence, they removed me immediately. When everything was doubted in my early education because I didn’t perform on grade level, I went to college anyways. I became a writer, photographer and English teacher.

When someone doubted me, it started a fire that, “That’s fine. I’ll prove you wrong” only to prove my true worth to me.

I had no control over the loss of Corrie or my miscarriage. I had no control when the colon cancer came. When a old man told Hayes at a recent football in a section where other students, including some of mine stood and cheered, to: “Sit down, and stop being a damn nuisance” out of my hearing; God protected this individual that night from John or I knowing his identity.

I remember Mr. Bernard’s words that Hayes shines a light in this world, whether individuals see it or not, yet. I remember two weeks ago, when it was warm outside in the afternoon, I’d left my coat in the classroom. Hayes went to get it, and said, “Mom, you need your coat for in the morning.”

When that man yelled at Hayes at the football game, he didn’t tell John and I until later because “I didn’t want Dad to go to jail, and he didn’t know I had autism.” When I broke down for the first time in a longtime because I felt like a complete and utter failure as a parent, Hayes got tissues. He took my phone, and called John. My husband coached him through it.

No, a child should not have to deal with caring for his parent. We, as a family, are learning through the fire.

We are reading together. He struggles with reading, but he reads more clearly at home away from the distractions of school. We also have that bond, as he had with previous teachers like Mr. Bernard.

We work in the yard together. As I type, he is blowing leaves.

Most importantly, I figured out what might be good for him. The acting teacher at our school is amazing, and she is one of the few that recently has seen his intelligence. She has praised him for it, and he has responded to her.

John went to a recent performance in his drama class, and filmed it for me. Then it clicked. A moment of sun in otherwise darkened room: put him on the stage.

He read and memorized lines. It was three, but he learned and performed him. He didn’t disrupt others performances as he might in a class. Why? Mrs. Shelia, as I’ll call my amazing co-worker here, built a bond. She is on the level with Mrs. Schaeffer, Mr. Bernard, his other elementary and sixth grade teachers. If I could, I’d choose her as our teacher of the year.

I plan to sign him up for acting classes with other kids his age closer to home. His love of old movies, scripts we’ll read at home, and being direct will hopefully help him with his purpose, reading and confidence.

Hayes was always my light when all others went out.

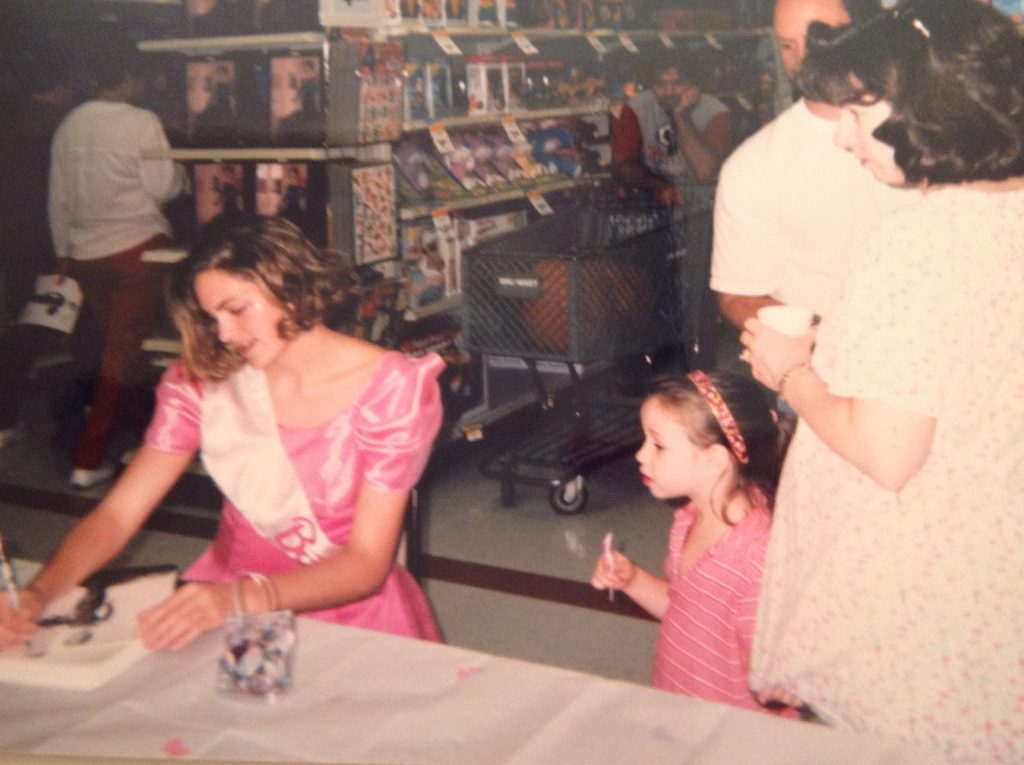

All pictures, except one, poetry excerpts, and words by R.A. Bridges