I don’t know how Alexander Hamilton and his wife, Eliza, did it.

There isn’t a record about the conversation they had with their younger children after the loss of their oldest son.

According to Ron Chernov’s Alexander Hamilton, the subject of his book and the famous play did write a poem in 1774 for his close friends after they lost their young daughter to “a fatal illness.” He wrote it from the mother’s perspective.

Today’s read is longer, but worth it as we consider the forgotten mourners.

What we share in common

Most people deal with death at some point.

Like weddings, career changes, or the announcement of a child’s birth; death is a thread which sadly connects us.

.

Some of us recall the moment our favorite family dog or cat died. Others remember the moment their first grandparent died.

No one wants to imagine a child facing the grief after death. Just as I wrote yesterday, child loss or even grief and mourning are topics, like autism, society needs to discuss.

As a child, I remember when each of my grandparents died, and how I was told. I recall the pain and heartbreak I felt. What I feel more deeply is speaking with my son about his losses.

1. ACKNOWLEDGING HIS LOSS

As my husband John says, there isn’t a guide book for how to live after you lose a child. “If there was, no one would read it.” While there are inspirational books and I read them, every person’s growth through grief and mourning is different.

Siblings are often called the “forgotten mourners.” Children are more resilient, and they also feel more deeply than adults realize.

In sixth grade, I faced bullying and my maternal grandfather’s hospitalization. In 1996, our Saturday and Sunday commitments changed. Usually a healthy man for most of his life, my grandfather, called “T.L.” or “Gramps,” suffered a minor stroke. A series of events in the hospital transferred him from the regular hospital rooms to the ICU.

I was either with my baby brother and cousins with an adult nearby or at the hospital. For what seemed like hours, I waited in the ICU waiting room as only one person was allowed to visit T.L. at a time. At the magic age of eleven, I somehow stepped across the uncomfortable line of adult experiences. I remembered one side of his face sloping .

Everything was still except for the nurses in the background and the beeps of the machines. All the blues and whites seemed to blend together. How could this happen when just a few weeks before he had gone with me to the state fair, I wondered.

I did this week after week until we received the phone call that T.L. was gone. I remembered the visitation, the smell of some stale perfume that never comes out of the carpet, and the body.

For years, I never talked about it because all of the adults were going through their own grief. I witnessed my grandmother’s questioning of God. I saw pure, unfiltered anger and anguish when I stayed with her after Christmas because it was thought I’d bring her joy.

But, I never forgot the loneliness and despair of loss as a child.

Knowing my experience, it is a small shadow of what Hayes, my son, has experienced. As a parent, I must acknowledge his losses. He prefers my death friendly phrases, such as “graduated to heaven” and “earned her wings.”

In the space of eighteen months, he lost two people he loved dearly: his grandfather and sister.

2. LET HIM TALK

Time to talk gives children and teens a voice.

They will reveal more to you if you don’t get angry the moment they discuss something. Sometimes they’re testing the water.

While I share some pictures and moments in regards to my son here, I keep the majority of what he has shared with me between us. He is coming to an age where the privacy of his voice is more important than ever.

Time for a child or teen to talk about death with you is extremely important.

If I stay in my worn shoes no parent wants to wear, then I fail to consider how my son feels. I fail to become an effective parent for a child experiencing grief.

Hayes has questioned why he lost his grandfather and his sister so close together.

For him, “Granddaddy” was one of the few immediate members of his father’s family he really got to know. Due to deeply divided differences, other members of my husband’s DNA have an alternate definition of family, and we accept it because my family and John’s sister are the very meaning of family.

At eight-years-old, my son went behind the adult men and picked a flower near the bell tower. He put it on his Granddaddy’s coffin.

“I want to honor him, too,” said my then eight-year-old son.

Then he sat in my lap under the green tent and cried. He let his thoughts flow.

When he talks about loss, he mentions Corrie and his Granddaddy together. Sometimes he includes our puppy, Jack, who passed in July, and recently his great aunt, my dad’s sister.

While he visited my aunt a handful of times, in his imagination, he saw her upstairs as a magical place.

When my Dad visited Corrie’s gravemarker, he called Hayes from the bell tower and gripped his shoulder.

He said, “We have something in common. We’ve both lost a sister.”

I saw the tears in Daddy’s eyes, and Hayes hugged his Papa. For my father to acknowledge Hayes’ losses was a powerful moment for both of them. Another adult, besides his parents, verbally spoke with him about it.

A lot of the times when Hayes talks to me about his feelings or his dreams we’re driving to school, from school, or we’re at the cemetery together.

3. allow his expression in your works

In one joint therapy session, Hayes’ therapist had us complete an illustration together. I do not claim to be an artist. At best, I draw a pretty rose. My lips and noses on people as a child were too big. I drew my flowers, and Hayes went blitzkrieg on my small portion of the illustration drawing all sorts of loop-the-loops.

In my typical, “Mrs. Bridges, I can never imagine you being the mother to small children” fashion, I rolled my eyes, and said, “You have your area over here.”

It was a rare occasion where we did something together, but I believe this is an important part of the mourning process, especially if you have a “forgotten mourner.” Children and teens need to feel included in what you or they’re doing to express their grief.

What grieving siblings really need is for adults to be open and honest with them about the death. And they need to know that their grief is important, too, and that their unique thoughts and feelings are acknowledged, too.

Alan Wolfelt

In two of my previous blogs, I’ve mentioned an author named Alan Wolfelt because his book Healing a Parent’s Grieving Heart presents practical advice in how you, as a parent, handle the pain. In his mini-chapter 7, he writes ways to “Be compassionate with your surviving children.”

One suggestion he made included not forcing your child to go with you to the cemetery because it could make the child uncomfortable. When I go weekly to the cemetery to check Corrie’s and my in-laws’ graves, I also look at the needs of my now twenty-nine babies, children and teens on my Kinder Memorial Walk. I recognize the emotional impact it can have on a child.

As I left yesterday the car to take the artificial poinsettia saddle to the family marker, I planned to leave Hayes playing on his swing set as his father blew leaves. I had planned to continue doing Christmas decorations at the house with him when I returned.

“I want to go,” he said.

“I’m not going shopping,” I said, “and I have a bunch of graves I need to serve.”

“I want to go,” he said.

“Alright.”

When he goes with me to the cemetery, I allow him to do most of the talking. He needs the space to express himself. With my son, it takes more digging because sometimes he speaks in metaphors. Sometimes he hints at a story or feeling, and I have to play guesswork. Without his sister who told me daily what other kids and teachers said to him at his previous after school program, I have to play investigative reporter.

This is part of his deep thinking. Hayes feels you out with a bunch of questions. Sometimes they seem inane and endless. Sometimes he is figuring out who to trust, and who he will not trust. I admit he has adopted some of my skepticism and cynical distrust of other people in general.

But I rather have him question others than easily give his trust.

When we go to the cemetery, the event is not to enforce what I do voluntarily onto him. Hayes chooses to go, but I also need to be open to include him. At times, I feel protective of the spaces in which I work, especially Corrie’s area.

4. The hAYES’ tOUCH

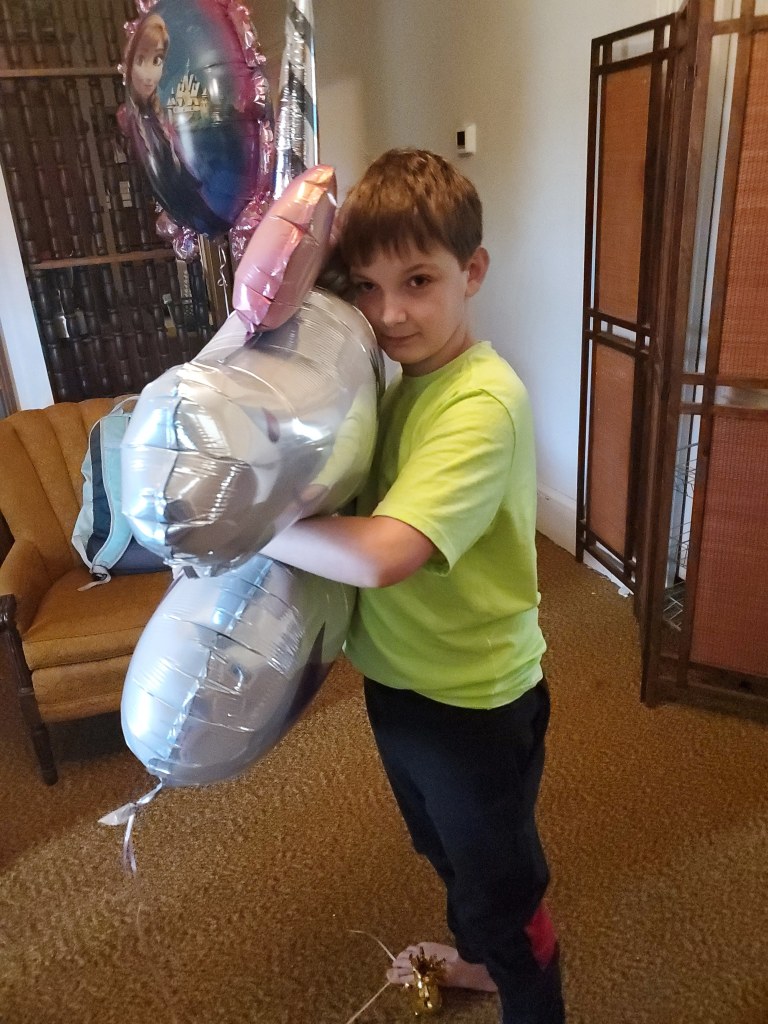

I include Hayes, when he wants to go, in my work at the cemetery. The picture above is a single example of debate between my son and me, along with compromises. The pink lines are what I wanted, and the yellow is his influence.

I wanted to put Corrie’s nutcracker next to her new floral holiday arrangement I did on Friday to give it an even look. Hayes put the nutcracker in front of her poinsettia. At first, I wanted to say:

“No, no, no,” but then I realized it looked cute, and I could put something else where I’d originally had her Thanksgiving fox.

Every week, I place a balloon at her site. Hayes put it directly behind the window, and I wanted it on the side. I let it go.

I bought five small Christmas trees. One was for Hayes, and the others were for the families in the Kinder Memorial Walk I serve with more than one deceased child. My sister-in-law had a unicorn Christmas tree for Corrie.

“We don’t need one for here then,” I said.

“Corrie needs a Christmas tree, too,” Hayes said.

“Okay.”

Then I needed something on the other side to make it look even. I put a poinsettia there.

Yesterday, I wrote why I share photos of the cemetery on social media because parents who have their children in life together share theirs all the time. Hayes and I discuss the changes we make at Corrie’s and their grandparents’ graves together. He has a voice in what we place there and where we locate it.

Before we left yesterday, Hayes found another infant’s grave near the ones I serve. I have sometimes trimmed it and dropped petals around it. He said, “This one isn’t decorated. It needs something.”

“I know, son, but I’m only one person,” I said. “I can only serve so many.”

In that moment, it was not that I could not do it. It was the fact my son noticed and felt the emotion.

By Rebecca T. Dickinson

It’s very noble of you to keep the departed in mind. Remembering them and including them honors their memory.

Reblogged this on Autism Candles.