There are times in this life when we feel the currents pull.

Maybe we go to the beach. We walk into the water. The ocean currents tug and pull. Someone told you, “Look, high tide is coming.”

Maybe you turn around, pack up your towel and return to your room or beach house.

Perhaps you go into the ocean anyway. You take the 18-year-old belief: I’m invincible. Nothing bad will happen to me.

The water brushes up against your legs, and splashes water up to your knee. You feel comfortable enough as you relax your feet in the sand.

The current tugs you. It pulls you in rocking you around in the water. You think: if I just get my footing, I’ll get out of this. But the water pulls you with more power than the strength in your legs. Waves pour over your head, and you feel the pressure in your lungs to breathe as you push against the water.

I’ve been there, too.

Because I walk in the tides.

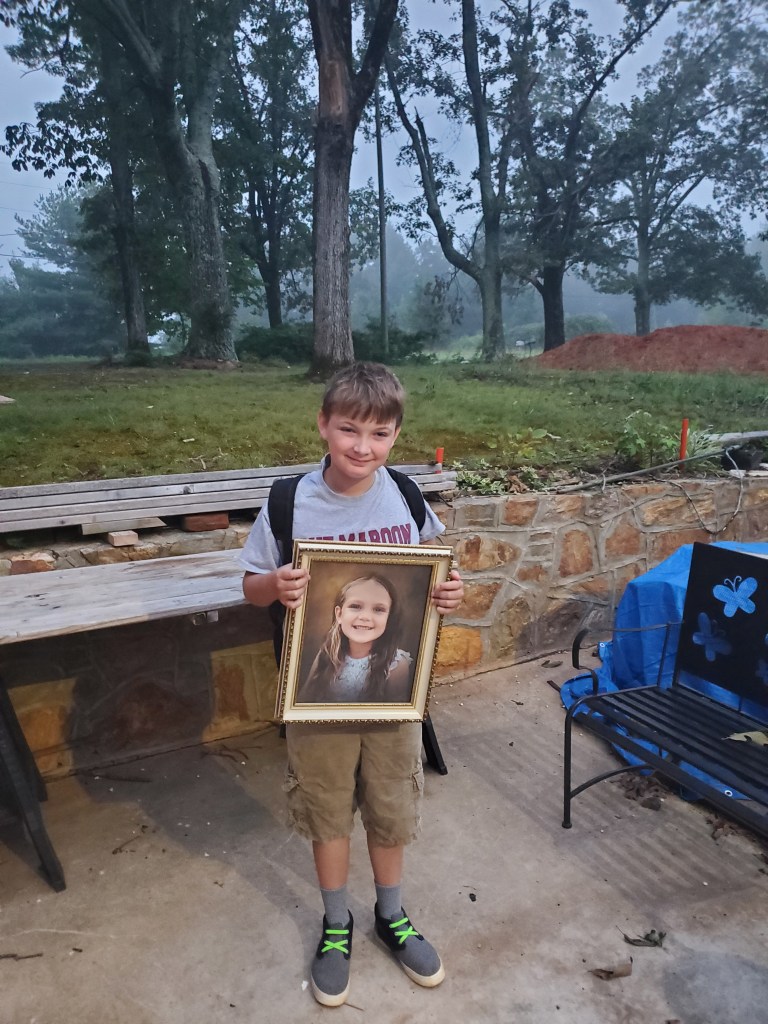

My son, Hayes, and I experienced every emotion from happiness, joy, anger, and despair during our first week back at school, and we felt them at one time. It is one thing to be a bereaved parent. It’s another to be a child with autism grieving the loss of his best friend and sister.

We’re getting back in shape physically, and we have been battered enough emotionally. We usually get stronger after we respond. We try not to react in anger as hard as that was when part of you is dead.

You cannot tell me I’m whole.

You cannot tell me all of me is living.

So long as one child walks this Earth and the other does not, I will exist with half of myself.

We are stronger than we look because the high tides continue to rise, yet the tests of our strength aren’t done.

Hayes started this week on Monday. He will return to elementary two days next week, and eventually a five-day-a-week if we’re fortunate to make it that far due to COVID-19.

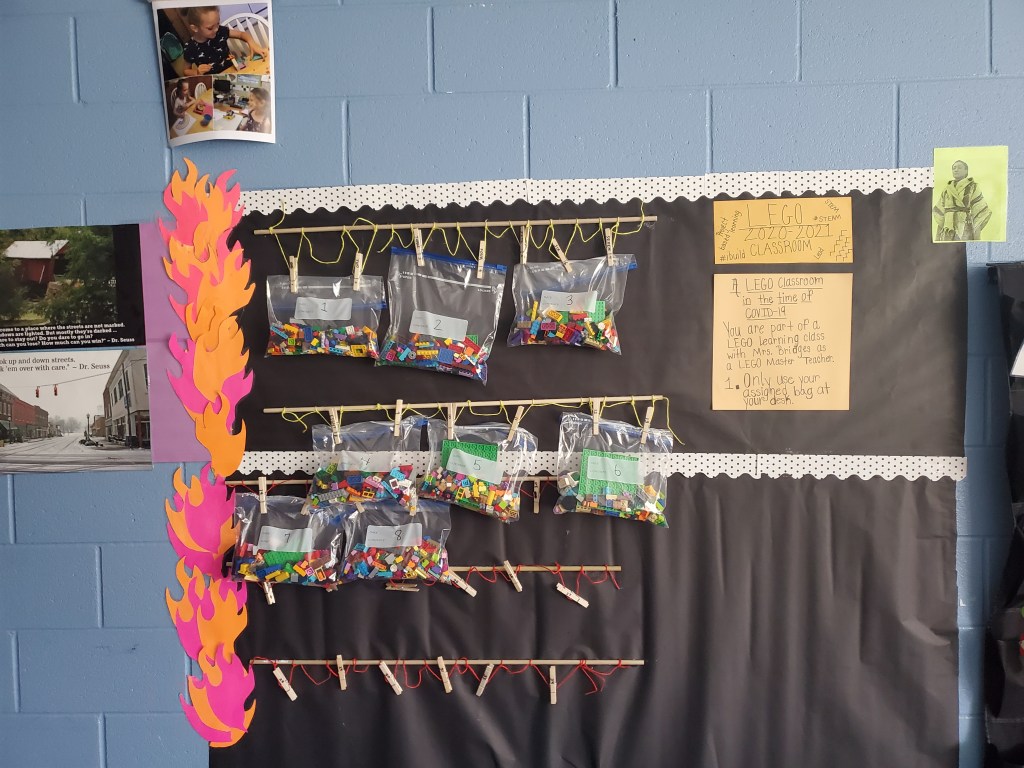

The first two and a half days at school went great for us. My first three days were what I had planned on. As a new LEGO Master Educator, I tied in hands-on learning on day 1 where each student completed a LEGO build of what they did this summer or their COVID-19 environment.

I did introduce the fact I am dealing with grief, so they would know when I step away. So they would know the girl Corrie I will occasionally mention. Then we discussed how it is okay to fall apart, but it is how we handle it that is important.

We did the classroom expectations,

the classroom and hallway protocol,

and the COVID LEGO protocol in which every student is assigned a single bag of LEGOs with a plate on which they build.

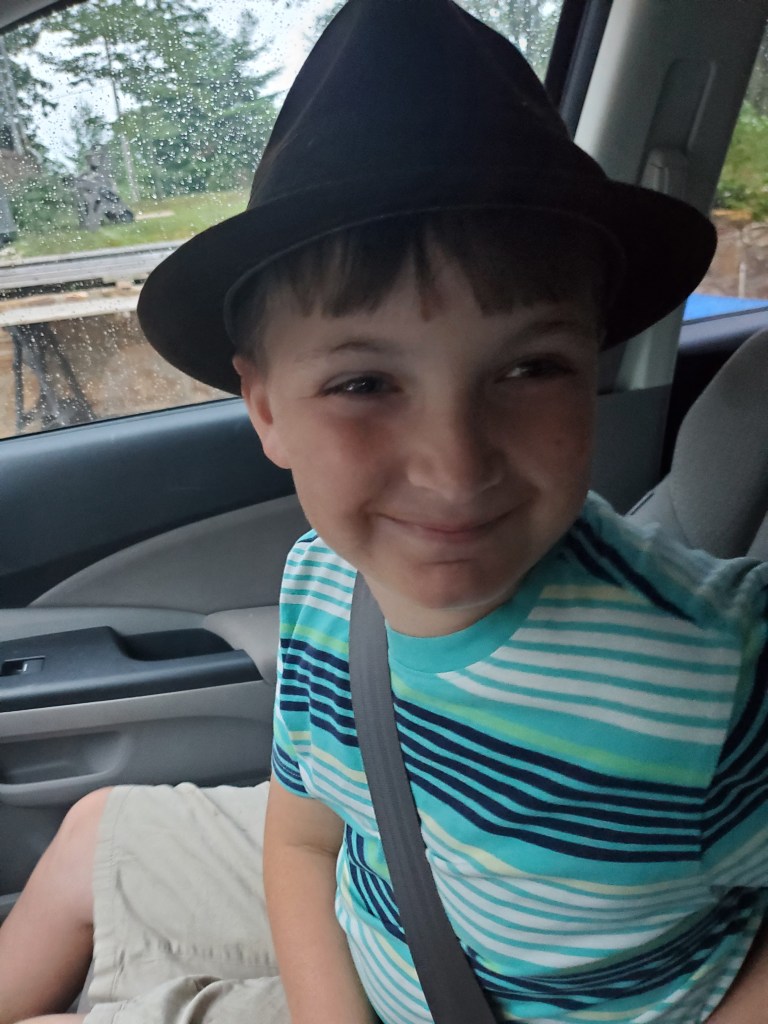

Wednesday was the first day I’d felt happy, since May 26, 2020. While I’d experienced moments of contentment, bittersweet joy, or laughed; I’d been divorced from happiness for a while. As Hayes and I went to school, Danger Zone came on the radio.

Me being me, I banged my head around as if I’m in an 80s’ band. Hayes joined me. We rode through backroads all the way to his after school where he had stayed, since he wasn’t scheduled to go to school everyday, yet.

I’d thought leaving him at the church school where Corrie had attended her last year of preschool would be good for him.

Don’t get me wrong. It is a great program for children five and younger. He originally went there after school, so long as his little sister attended. When she joined the big kids in the after school program, she was quick to stand between him and other children bigger than her who teased and sometimes bullied Hayes.

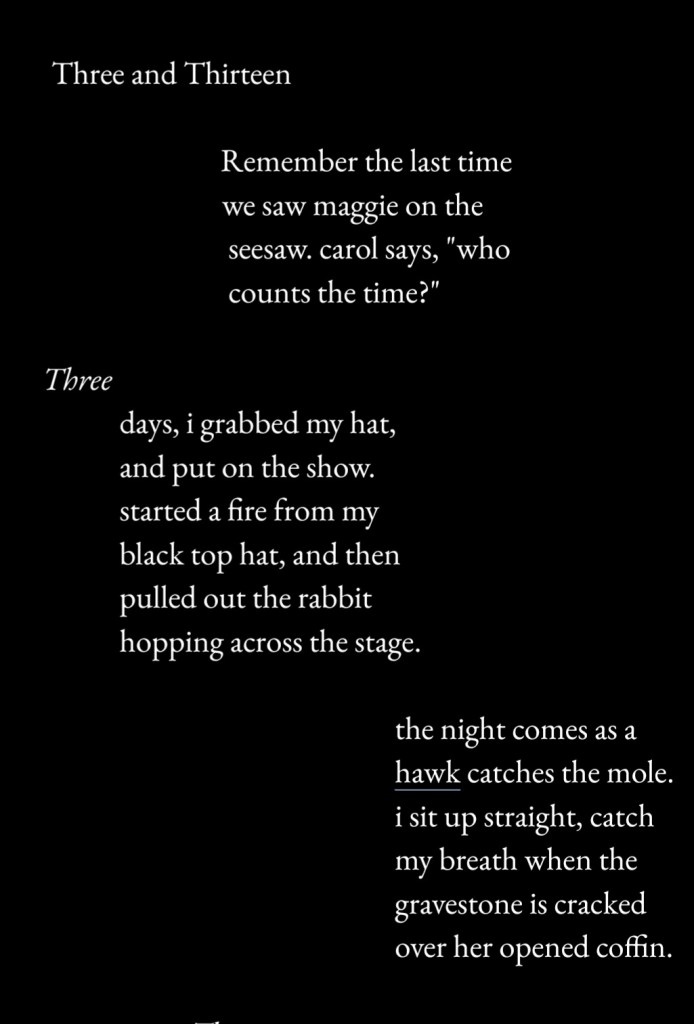

The poem I wrote the other day, Three and Thirteen, covered not one but several different events, and was about many different people and things in the storm surrounding our grief over Corrie’s death. Even the name “Carol” in the poem does not represent one person. It is more a combination of fear, people, and the idea the world will move on and leave deceased children like Corrie and the little girl, “Maggie,” in the poem behind. I even leave Is and certain names lowercase on purpose because that is how insignificant we can feel sometimes.

Proper nouns and pronouns work for proper times and places along with Standard American English. But they don’t work for a torn up heart.

When I picked up Hayes on Wednesday, my great day smile quickly disappeared when I saw his face. His face is just like mine because I was a child just like him.

One teacher from the program quickly told me the actions Hayes had taken.

My son is not perfect. He misbehaves, and my husband and I always hold him accountable.

Hayes misbehaved. He made other children uncomfortable, and said something extremely inappropriate to the after school group’s teacher who’d joined the program at the beginning of summer.

Before I could turn around, the one teacher Hayes had bonded with also told the story.

Tears streamed.

The tides came over me. They pulled me below the waves and rolled me around. I felt a swarm of emotions I’d never felt before at one time.

Anger with my son.

Anger with this after school teacher who’d never talked to me.

Despair that the place Corrie loved so dearly and had meant so much to our family might be tarnished.

The teacher with whom Hayes was close said that she’s held the other teachers back. They’d been giving him a break “because of Corrie.” She told me further that teachers were ready to jump back in to full time punishment. She said she’d recommended to the other teachers that they needed to ease into it. She said next time he did anything like that he would be expelled.

Furthermore, they were coming to me for suggestions to help the after school teacher.

I wanted to throw up all over the place.

How could I give you suggestions when I rely on you to be the teachers like the ones with whom I work or his school teachers who have behavior prevention in place?

In what the teacher, to whom he was close, explained:

“I know that’s not Hayes. I saw him on the playground like he was looking for her. You know, he’s loner most of the time.”

I wondered why, if this teacher had had issues with my son, why didn’t she contact John or I when she had our numbers?

I heard everything he’d done second hand.

I’ve also watched my son with other children long enough to know that sometimes they try to influence him to say certain things for shock value. He is by no means innocent. He will say things on his own for shock value to test adults, especially if he feels ignored or unloved by the adults.

He would not tell me during the summer while he went to camp and into the new school year that he wanted to stay home or with me. I did not know all the reasons why because he’d say: “I don’t know.”

Corrie always told me who did what, who said what, and what they did not do.

I didn’t know what to believe because I know my son’s story is not 100 percent accurate anymore than this mysterious after school teacher who has never once attempted to contact me, one of the easiest parents to work with.

He said, “She yells at me all the time.”

I got the feeling after a field trip when a boy told Hayes inappropriate things about me that the child himself did not understand, he was not wanted by the program or the teacher.

Hayes did not tell me everything that happened because he knows I will turn into a lionness. He doesn’t know how to always put his emotions into words.

But I have lived the story before:

She is often described as being very aggressive and abusive with her classmates, often hitting other children for no apparent reason. [Mathilda] has been unable to identify the source of her problem … she has been described as having great difficulty in interacting with her peers and … is said to be rejected by her peers more so than other children.”

From Rebecca Dickinson’s Neurodevelopmental Evaluation Summary, Page 3

The little church school was made for Corrie, has places in its garden in memory of her, and a beautiful corner in the preschool in memory of her. I will continue to donate toys to the preschool on Corrie’s and my birthday because this part of the school is a wonderful program. I adore Corrie’s teacher, and wish there were more like her.

I took him out of the school as soon as I got home. He opened up about how miserable was, and lined up the Y.

Corrie had made noises before her death about how she wanted “to go to the Y with the big kids” once she would have started Kindergarten.

The thing is the world was made perfectly for children like Corrie.

Not for Hayes.

But where Corrie was, she always included Hayes.

After I resolved to move him to the Y.

I believed the waters were calm again.

I am so tired of times when I start to feel content or happy, and a sword is plunged into my gut.

That is what happened when I read the words “your dead kid” the following day.

I cannot and won’t reveal the circumstances of it, but it set me off.

I went from sadness, to anger, to talking to a few people for advice to thinking that no, I revealed to much of myself because they will never, nor should know, this pain.

Then it got worse.

It was a feeling of never being able to say her name again or people would get tired or sick of me talking about her. Or, worse like the school with Hayes, it’s time to get back to normal.

It’s time to move on.

The fear of that attitude was what Carol represented in my poem, Three and Thirteen, for both Hayes and me.

Am I really expected to live in a world where memories of my Corrie are restricted?

Am I expected to let her name vanish and for her to be viewed as a “dead kid”?

Is she really just a dead kid?

Do you know what it is like to read those words about the child you carried for nine months, nursed and raised?

I have been insulted to my face about my son during his early childhood, so I am accustomed to this. Not for my daughter.

It is like watching the funeral director close your child’s casket.

It is like this:

I am going to be honest with you.

I was pulled under the high tides. I could not find my feet.

Why?

Because I had finally been happy for a day and I was robbed of it.

Because I could not fathom being where my Corrie was just seen as a “dead kid” and her name vanished without a care.

Where it went from beauty:

to

Why share something this deep?

Because imagine all of the other parents across the world who feel this way about their child or baby.

Imagine I am not the only one.

Imagine how many fear the world will push them to move on and forget their child.

Because mental illness is real, and it is not something you can shove into a closet and hide.

I walk the tides.

When I sit at a child’s grave, I blow bubbles sometimes. I say, “Your life was important.”

Someone very unexpected came in the moment when I felt done with the world. He forced me out of my self‐isolation. He never knew how deep I was hurting.

If you really want to help me or someone like me, then ask me when the time is right about Corrie.

Ask me about her favorite colors because purple is not enough.

Or tell me a memory you have.

Do not leave her memory or name unadorned like:

This a baby’s grave marker I plan to replace one day. This baby earned wings in the last 10 years.

If you caught it in the poem I wrote Thursday after all this happened, I referenced the hummingbird. The blue green hummingbird is what Corrie has sent me in a dream. I saw it one hour before I got my tattoo. I saw it again above baby Alexander’s grave. In the poem, I beg for the hummingbird because it is the hope Corrie sent.

I found it at the next child’s grave I will tend to; a grave where someone did exactly what I do now.

I walk the tides. My strength comes when I can summon Corrie’s spirit within me.

Then I felt better the second part of Friday. Hayes told me how he played soccer on Wednesday. I’ve never heard the words soccer, played, and fun in the same sentence from my son. On Friday, he played kick ball and soccer before he went to swim.

Words and photos by Rebecca T. Dickinson

1 thought on “I Walk in the Tides”